A MEDITERRÁN KÖNYVTÁRAK TÖRTÉNETE

(2024 szepember)

ABSTRACT:

Legnevezetesebb könyvtárak: az eblai (i. e. 2300 körül Szíriában) és a ninivei (bár nem mediterrán, de nevezetes és i. e. 600 körüli) könyvtárak, az antiochiai könyvtár, ami egy nyilvános könyvtár volt a 3. században. Az athéni könyvtár, a Ptolemaiosz könyvtár, amely az alexandriai könyvtár lerombolását követően lett jelentős, a Pantainos könyvtár i.sz. 100 körül; Hadrianus könyvtára i.sz. 132-ben.

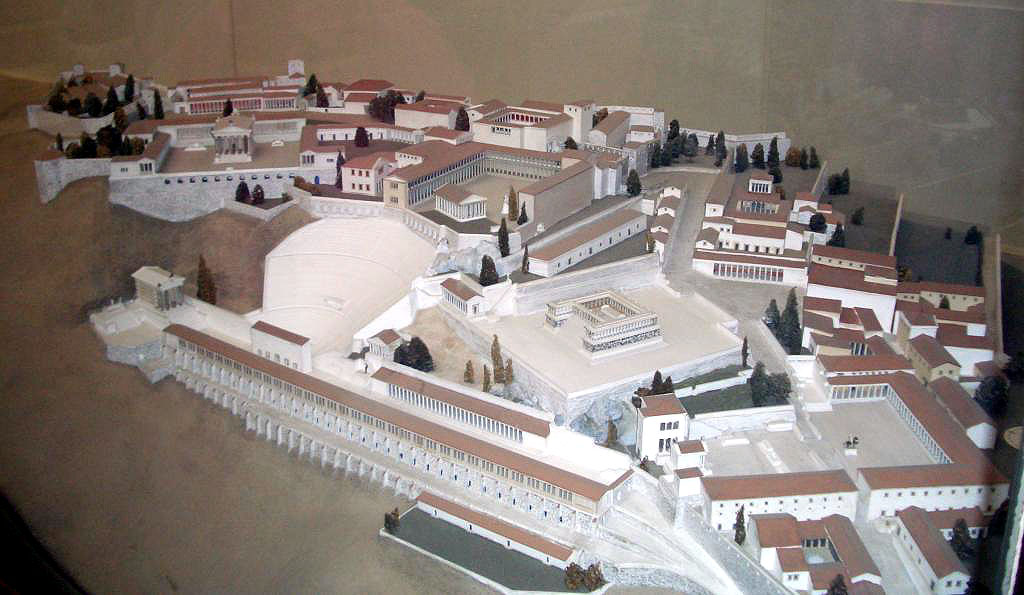

A pergamoni könyvtár, amelyet I. Attalus alapított; 200 000 kötetet tartalmazott, amelyeket Marcus Antonius és Kleopátra a Museion elpusztítása után a Serapeionba költöztetett. A Serapeion 391-ben részben megsemmisült, az utolsó könyvek pedig i.sz. 641-ben tűntek el az arab hódítást követően.

A Rodoszi Könyvtár az Alexandriai Könyvtárral vetekedett. Az alexandriai könyvtár, egy Ptolemaiosz Soter által létrehozott könyvtár 500 900 kötetet tartalmazott (a Museion részlegben), és 40 000 kötetet a Serapis templomban (Serapeion), ahol az egyiptomi látogatók poggyászában lévő összes könyvet átvizsgálták, és lemásolták. A Museion i.e. 47-ben részben megsemmisült. // THE HISTORY OF THE GREAT MEDITERRANEAN LIBRARIES: The most notable libraries are: the libraries of Ebla (c. 2300 BC in Syria) and Nineveh (c. 600 BC), the library of Antioch, a public library in the 3rd century BC. The Library of Athens, the Ptolemaic, which became important after the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, the Library of Pantainos, a public library in Athens, was a public library in the third century BC. A.D. 100; Hadrian's library, the Panteion Library, around A.D. 132 AD.

The library of Pergamon, founded by Attalus I; it contained 200 000 volumes, which Mark Antony and Cleopatra moved to the Serapeion after the destruction of the Museion. The Serapeion was partially destroyed in 391 AD, and the last books were destroyed by the Roman Emperor Antony and the Roman Emperor Antony in A.D. In 641, the Serepion was destroyed in 391 and the last remains were lost in 641 following the Arab conquest.

The Library of Rhodes rivalled the Library of Alexandria. The Library of Alexandria, a library created by Ptolemy Soter, contained 500 900 volumes (in the Museion section) and 40 000 volumes in the temple of Serapis (Serapeion). All the books in the luggage of Egyptian visitors were examined and copied. The Museion was partially destroyed in 47 BC.

The Library of Rhodes rivalled the Library of Alexandria. The Library of Alexandria, a library created by Ptolemy Soter, contained 500 900 volumes (in the Museion section) and 40 000 volumes in the temple of Serapis (Serapeion). All the books in the luggage of Egyptian visitors were examined and copied. The Museion was partially destroyed in 47 BC.

BEVEZETÉS

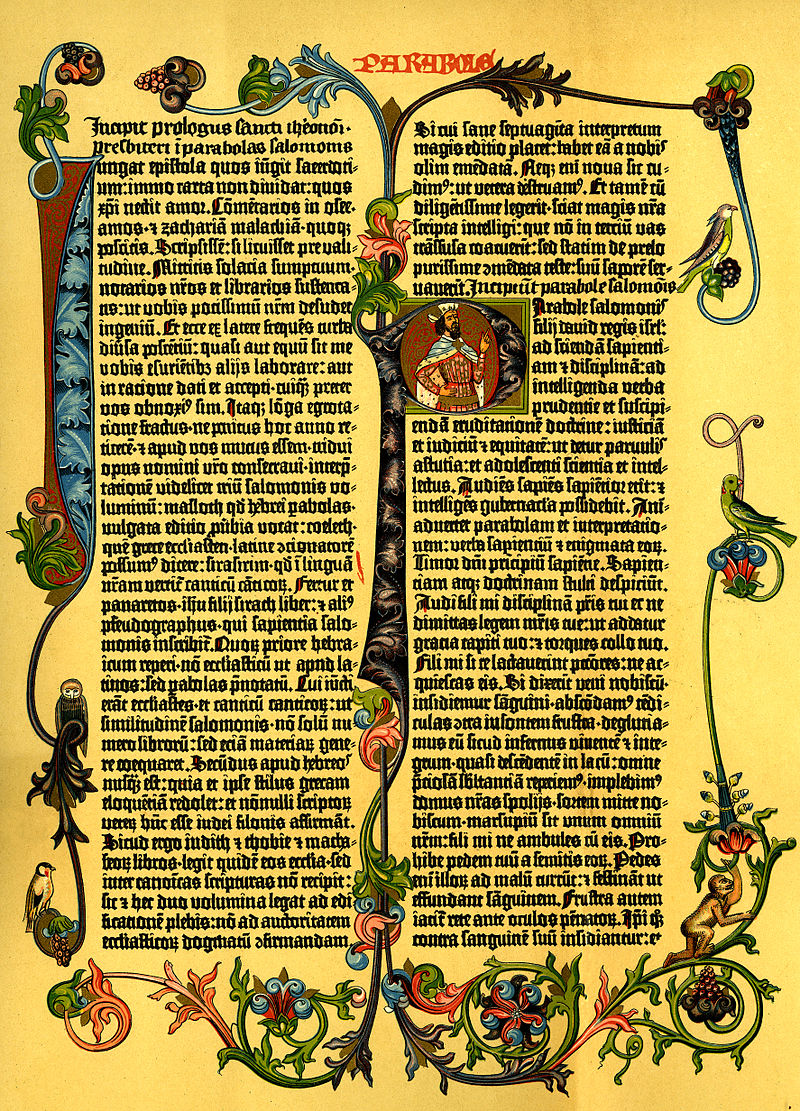

A könyvek történetével kapcsolatos legkorábbi írások a kőtáblákkal (sztélékkel), tekercsekkel és papiruszlapokkal kezdődnek. A jelenlegi, általunk könyvnek tekintett formátumot, amelyben külön lapok vannak egymáshoz erősítve, kódexnek nevezik. Kódex formájában jelentek meg a kézi kötésű, drága és bonyolult kéziratok. A kódexek Gutenberg idejétől átadták a helyüket a sajtóban nyomtatott köteteknek, melyek végül a ma elterjedt tömegnyomtatott kötetekhez vezettek. A kutatás módja az internetes keresés volt, célja az ismeretterjesztés.

Az írásokat a legkorábbi anyag szerint kőtáblákra vésték, majd az ókorban agyagtáblákra, pálmalevelekre és papiruszra írták. Később a pergamen és a papír vált a könyvkészítés, kéziratok alapanyagává, pl. a dél-ázsiai Mogul-korszakban. A nyomdagép feltalálása előtt (a Gutenberg-biblia előtt) minden szöveg egyedi, kézzel készített értékes írás volt, amelyet az írnok, a tulajdonos, a könyvkötő és az illusztrátor a megrendelő kívánsága szerint készített el. A nyomdagép 15. századi feltalálása forradalmasította a könyvkészítést. A papirusztekercset latinul „kötetnek” nevezik. A tekercsek esetén néha egy, de általában két függőleges fatengelyre tekercselték fel a pergament. A kialakítás miatt a szöveget csak írási sorrendben lehetett elolvasni, az olvasónak mindkét kezével fognia kellett a függőleges fatengelyeket.

A Gutenberg-biblia egy lapja (https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Gutenberg).

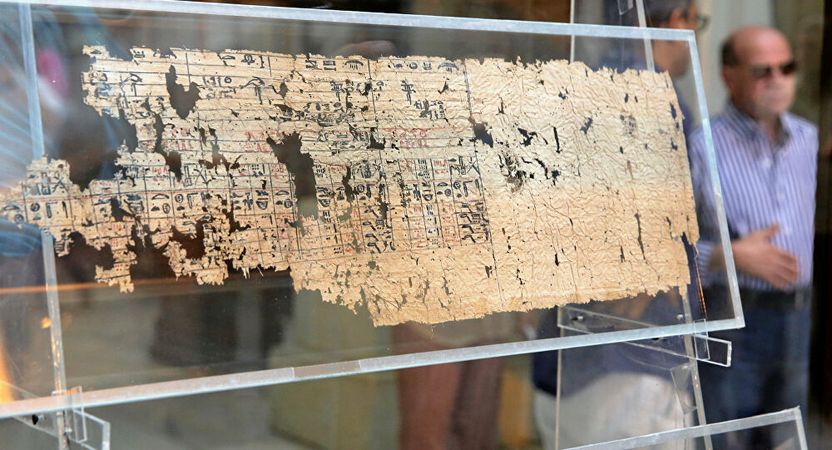

Az első papirusztekercs

Egy Merer nevű munkavezető hieroglif jelekkel írt naplóját találták meg, i. e. 2570 körül írták, (Diary of Merer, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diary_of_Merer), amely napi beszámoló a Níluson keresztül történt kőszállításról, a Tura-i mészkőbányából a Nagy piramis kikötőjébe (Ra-shi-Khufu-ba), Gizába. Ideje: Hufu fáraó uralkodásának a végéről júliustól novemberig, napi bontásban. Július 17.- a körül volt az áradás, ekkor telt meg vízzel a piramishoz ásott csatorna. A naplót Pierre Tallet és and Gregory Marouard találták meg a Wadi el-Jarf nevű Vörös-tengeri kikötő barlang-raktárában. A P. Tallet úgy gondolja, hogy a Nagy piramist fedő köveinek szállítására vonatkozik a napló. 10 naponként 2-3-szor fordult a csapat, 200 darab kb. 2.5 tonnás követ szállíthattak havonta a turai kőfejtőből Gizába. A több mint 100 tagú csapat 40 hajósból is állt. Egy hajó 5-10 db követ szállított. A napló alapján következtetni lehet az Egyiptomi Birodalom szervezettségére, logisztikájára: sok csapat szinkronizált tevékenysége volt szükséges a piramis köveinek szállításához, építéséhez, akik közül az egyik a közel 200 kilométerre lévő kikötőben, Wadi el-Jarfban is tevékenykedett. Az egyiptomi adminisztráció magas szinten történt szervezettségét bizonyítja a papirusz.

Az i.e. 2570 körüli papiruszt ilyen állapotban találták meg, talán a legrégebbi (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_papyri_from_ancient_Egypt)

(Diary of Merer, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diary_of_Merer)

A könyvtárak gyakran a háborúk és a tűz áldozatává váltak, a kulturális konfliktusok is a könyvek pusztításához vezettek: 303-ban Diocletianus császár elrendelte a keresztény szövegek elégetését. A keresztények eretnek, vagy nem kanonikus szövegeket égettek fel. A könyvégetések mára véget értek, néhány egyedi esettől eltekintve.

Legnevezetesebb könyvtárak: az eblai és a ninivei könyvtárak, az antiochiai könyvtár, ami egy nyilvános könyvtár volt a 3. században. Az athéni könyvtár, a Ptolemaiosz, amely az alexandriai könyvtár lerombolását követően lett jelentős, a Pantainos könyvtár i.sz. 100 körül; Hadrianus könyvtára i.sz. 132-ben.

A pergamoni könyvtár, amelyet I. Attalus alapított; 200 000 kötetet tartalmazott, amelyeket Mark Antonius és Kleopátra a Museion elpusztítása után a Serapeionba költöztetett. A Serapeion 391-ben részben megsemmisült, az utolsó könyvek pedig i.sz. 641-ben tűntek el az arab hódítást követően. A Rodoszi Könyvtár az Alexandriai Könyvtárral vetekedett. Az alexandriai könyvtár, egy Ptolemaiosz Soter által létrehozott könyvtár 500 900 kötetet tartalmazott (a Museion részlegben), és 40 000 kötetet a Serapis templomban (Serapeion). Az egyiptomi látogatók poggyászában lévő összes könyvet átvizsgálták, és lemásolták. A Museion i.e. 47-ben részben megsemmisült.

A könyvtárak története

A dokumentumgyűjtemények rendszerezésére tett első törekvésekkel kezdődik a történet. Az érdeklődésre számot tartó témák és nyelvek szerint (oklevelek, vallásos szövegek, raktár- és adólisták, költemények) rendszerezték az írásokat, és az anyaguknak megfelelően (agyagtábla, pergamen, papirusz) raktározták az írásokat.

Korai könyvtárak

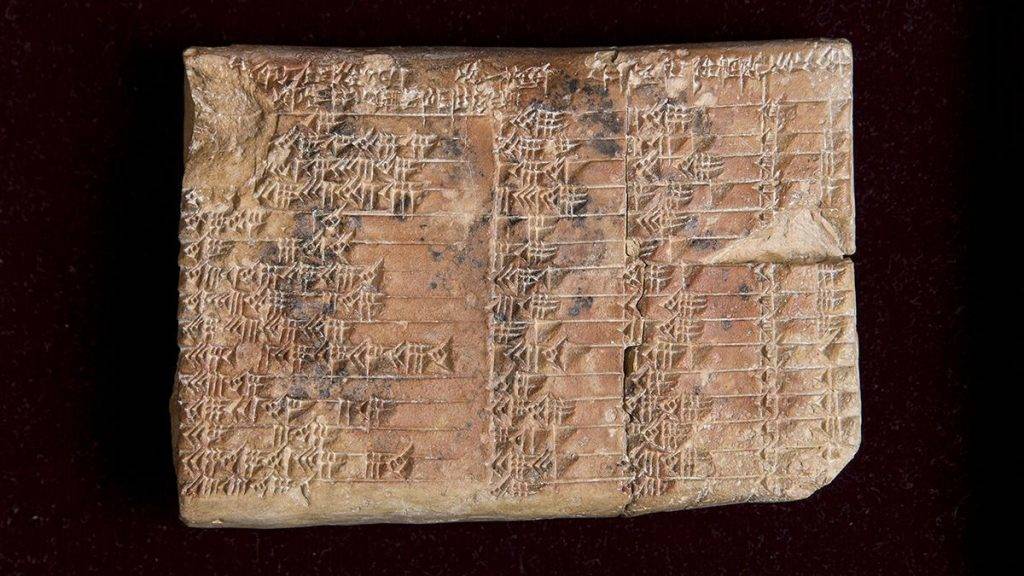

Az első könyvtárak az írás legkorábbi hordozóinak, az agyagtábláknak az archívumaiból álltak, a mai Szíria területén. Eblában felfedezett (https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ebla) ékírásos agyagtáblák; és a templomi szobák agyagtáblái Sumerben, a mai Irakban, e kettő a legrégebbi. A körülbelül egy hüvelyk vastag tabletek különféle formájú és méretűek voltak. A fakeretekbe sárszerű agyagot helyeztek, a felületet az íráshoz lesimították és hagyták részben száradni. Feliratozás után az agyagot napon kiszárították, vagy kemencében kiégették. Tárolás céljából a tableteket egymás mellé lehetett állítani, a széleiket tartalommegjelöléssel. Az archívumok főként kereskedelmi tranzakciók vagy készletek feljegyzéseiből álltak. Az ókori Egyiptom papiruszain található kormányzati és templomi feljegyzések hasonlóak tartalmúak. Az eblai királyi palotában több mint 14 500 ékírásos táblát találtak, amelyek eblai nyelven és sumer ékírásos jelekkel írtak. A táblákat élére állítva polcrendszeren tárolták. Háromnegyedük adminisztratív szövegeket tartalmazott, de voltak közöttük sumer és eblai nyelven írt irodalmi művek is. Az egyik irat szerint egyik királyuknak 80 000 juha volt, és minden évben 5 kg aranyat, valamint 500 kg ezüstöt kapott. Egy alabástrom edényfedőn megtalálták I. Pepi (i. e. 2332 – i. e. 2283) egyiptomi fáraó kartusát, ami segít az eblai civilizáció datálásában.

Babilóni agyagtáblák: 4000 éves írások találhatóak az ókori babiloni ékírásos táblákon, amelyek több mint egy évszázada lefordítatlanok, műzeumok zulajdonai, széthordták a táblákat. A British Mózeumnak van az egyik legnagyobb gyújteménye. Az agyagtáblákba vésett szerződésekből, hagyatéki felsorolásokból, adózási iratokból kiderül sok minden Babilónról. Az is, hogy a Mezopotámiába hurcolt, vagy a katonákkal önként távozó zsidók sok száz évvel száműzetésük után is még a héber dátumokat használtak, generációkon át megtartották a héber neveiket is. (https://m.mult-kor.hu/a-zsidok-babiloni-fogsagat-dokumentaljak-az-ekirasos-agyagtablak-20150204), és az is, hogy egyes holdfogyatkozások miként a pusztulás és a járvényok előjelei voltak. Az agyagtáblák készítői az ómeneket a holdfogyatkozások dátuma, hossza, a bekövetkezésük éjszakai időszaka, és az árnyékok mozgása alapján jelezték előre. Babilonban és Mezopotámia más részein elterjedt volt a hit, hogy az égi események alapján a jövő megjósolható.

Érdekesség: (https://matekarcok.hu/a-babiloni-matematika/, https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babiloni_matematika), A matematikát eleinte csak gyakorlati célokra használták: árucikkek darabszámának feljegyzésére, az értük járó pénz kiszámítására. Később geometriai, algebrai feladatokat oldottak meg vele. A babiloni csillagászat hatvanas számrendszert használt. A babiloni matematikusok képesek voltak számokat összeadni, kivonni, szorozni, osztani. Számításaikhoz segédtáblázatokat vettek igénybe, melyek tartalmazták a számok négyzeteit 1-től 59-ig, továbbá a 80, 90, 100, 200, 225 négyzeteit. Volt reciprok táblázatuk (mivel az osztás elvégzéséhez a reciprokkal való szorzást alkalmazták). Létezett a számok köbét tartalmazó táblázatuk. Létezett továbbá a számok négyzetgyökét és köbgyökét tartalmazó táblázatuk is. A négyzet- és köbszámok összegeit tartalmazó táblázatokkal is rendelkeztek. Ha egy számérték nem volt megtalálható a táblázatban, a gyök közelítéséhez interpolációs módszert alkalmaztak, ami átlagoláson és osztáson alapult. A módszer elég gyors volt, öt iteráció után 26 decimális jegynyi pontossággal megkapták a keresett értéket.

Érdekesség: (https://matekarcok.hu/a-babiloni-matematika/, https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babiloni_matematika), A matematikát eleinte csak gyakorlati célokra használták: árucikkek darabszámának feljegyzésére, az értük járó pénz kiszámítására. Később geometriai, algebrai feladatokat oldottak meg vele. A babiloni csillagászat hatvanas számrendszert használt. A babiloni matematikusok képesek voltak számokat összeadni, kivonni, szorozni, osztani. Számításaikhoz segédtáblázatokat vettek igénybe, melyek tartalmazták a számok négyzeteit 1-től 59-ig, továbbá a 80, 90, 100, 200, 225 négyzeteit. Volt reciprok táblázatuk (mivel az osztás elvégzéséhez a reciprokkal való szorzást alkalmazták). Létezett a számok köbét tartalmazó táblázatuk. Létezett továbbá a számok négyzetgyökét és köbgyökét tartalmazó táblázatuk is. A négyzet- és köbszámok összegeit tartalmazó táblázatokkal is rendelkeztek. Ha egy számérték nem volt megtalálható a táblázatban, a gyök közelítéséhez interpolációs módszert alkalmaztak, ami átlagoláson és osztáson alapult. A módszer elég gyors volt, öt iteráció után 26 decimális jegynyi pontossággal megkapták a keresett értéket.

Babiloni agyagtábla (https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/23/science/23babylon.html)

Mari-i agyagtáblák (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mari,_Syria): Zimri-Lim felégetett könyvtárában több mint 25 000 akkád nyelven írt táblát találtak, amelyek egy kb. i. e. 1800-1750 közötti 50 éves időszakból származnak, és a királyságról, annak szokásairól és az akkoriban élt emberek neveiről adnak tájékoztatást. 3000-nél több levél, a többi közigazgatási, gazdasági és bírósági szövegeket tartalmaz. A megtalált táblák szinte mindegyikét Mari függetlenségének utolsó 50 évére keltezték, és a legtöbbjüket már kiadták ma. A szövegek nyelve részben akkád, de a tulajdonnevek és a szintaxisban található utalások azt mutatják, hogy Mari lakóinak közös nyelve az északnyugat-sémi nyelv volt. A megtalált táblák közül hat a hurri nyelven készült.

Ugarit Latakia (Szíria, https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ugarit) mellett talált kikötő és város. Ugarit az i. e. 12. századtól kezdve lakatlan volt, így a későbbi építkezések, a lakosság nem bolygatta a régészeti rétegeket. A szíriai térségben is feltűntek az amoriták, azaz a „nyugati sémik”, akik Mezopotámiában is átalakították az eszközkultúrát, a nyelvet, a művészeteket és az államközi politikai életet, megbuktatva az új reneszánszát élő sumer államiságot, a III. uri dinasztia hatalmát. Az i. e. 2. évezredben a szíriai térségben, erős államok alakultak, Kizzuvatna és Jamhad, majd a Hettita Birodalom lett Ugarit szomszédja. A hettiták Mezopotámiában az amorita Óbabiloni Birodalomat döntötték meg. A óhettita kort összeomlás követte, ekkor a hódító szerepet a hurrik vették át. A rendszeresen bekövetkező északi és keleti támadások egyiptomi szövetségkötésre kényszerítették az ugariti uralkodókat, erős volt az egyiptomi hatás.A középbirodalmi fáraók sztéléi és szobrai jelentek meg. Zimri-Lim levéltára is említi Ugaritot, és már minószi áru is megjelenik. Az ugariti fellegvár Baál-temploma is ekkor épült. A királyság az i. e. 15–14. században élte fénykorát, bár az Amarna-levelek alapján Egyiptom vazallusa volt. Kereskedelmi flottája a térség legnagyobbja, a város népességszáma és területe is növekedett. Ebben a korban jelentős mükénéi görög kolónia is létesült. A ciprusi réz forgalma, a fakereskedelem, a Hattiba irányuló gabonaközvetítés, só, bor és illatszerek szállításán gazdagodott meg Ugarit, mert a tengerhajózás nagyot fejlődött. I.e. 1180 körül az akháj tengeri népek elpusztították.

Összesen öt nagy levéltár került elő, egész könyvtárnyi irodalmat találtak, majd további 120, és 300 darab újabb tábla került elő. A táblákon hét nyelv forrásai olvashatóak. Az ugariti nyelv a város a feltárás előtt ismeretlen volt, a nyelvemlékek az első betűírásos szövegek, az ékírás egyszerűsödésének utolsó fázisát képviselik. Nemcsak a diplomáciai levelezés fontos, hanem az óföníciaiak költészetét és mitológiáját is megismerhettük. Az ugariti a sémi nyelvek egyike volt, és a klasszikus héberrel, az ótestamentum nyelvével áll rokonságban.

Az Ashurbanipal Könyvtárból (https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assur-b%C3%A1n-apli) több mint 30 000 agyagtáblát fedeztek fel Ninivében, i. e. 600 körüli. A szövegek mezopotámiai irodalmi, vallási és adminisztratív témájúak. A leletek között szerepel az Enuma Elish, más néven a Teremtés eposza, amely a teremtés hagyományos babiloni. amorita leírását tartalmazza, a Gilgames-eposz, amely számos „ómen szöveget” tartalmaz, köztük Enuma Anu Enlilt, amely "előjeleket tartalmazott a Holddal, annak láthatóságával, fogyatkozásaival, bolygókkal és állócsillagokkal való együttállásával, a nappal, koronájával, foltokkal és napfogyatkozásokkal, az időjárással, nevezetesen a villámlással, mennydörgéssel és felhőkkel, valamint a bolygókkal és azok láthatóságával, megjelenésével kapcsolatban", továbbá csillagászati/asztrológiai szövegeket, valamint az írnokok és tudósok által használt szabványlistákat, mint a szavak listái, kétnyelvű szókészletek, jelek és szinonimák listái, valamint orvosi diagnózisok listái. A táblákat különféle tárolóedényekben, például fadobozokban, szőtt nádkosarakban vagy agyagpolcokon tárolták. Téma és méret szerint rendezték az agyagtáblákat. A szűkös könyvespolc méretek miatt a régebbi táblákat eltávolították.

A legkorábban felfedezett magánlevéltárakat az amorita Ugaritban találták, agyagtáblákon. Levelezést, és a leltárak mellett a mítoszszövegeket és a diákok írástanítására szabványosított gyakorló szövegeket találtak, és az első ábécét is. Az ugaritiak-főníciaiak alfabétája a görög szigetvilág közvetítésével, megszépült formában az itáliai Kümében jelent meg a kontinensen. Az ischiai (Nápolyi-öböl) múzeumban megtekinthető a Nestor kehely, amin a küméi ábécé első görög nagybetűit megtalálták.

Küméi görög felírat (https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C3%B6r%C3%B6g_%C3%A1b%C3%A9c%C3%A9)

"A latin ábécé, a világ legelterjedtebb és legpraktikusabb írásrendszere több mint 2500 esztendős múltra tekint vissza. Alapjául a nyugati görög írásnak az a változata szolgált, amelyet Chalcis városából való görög telepesek az i. e. VIII. század körül hoztak magukkal Dél-Itáliába." Kümén (Cumaeang) keresztül honosodott meg Itáliában a Cumaei ábécé néven, amit később átvettek a rómaiak is. A küméi kolónia az i. e. 6 században a vidék legbefolyásosabb városa volt, fennhatósága alá került Puteoli, Misenum, majd Nápoly is. Csak a nagybetűs ábécét használták, kisbetűs csak később, a középkorban alakult ki. A latin/görög ábécé az ugariti/föníciai ábécéből fejlődött ki, és lett az alapja sok más írásrendszernek.

Klasszikus időszak

A klasszikus korszakot megelőzi egy "Sötét kor"-nak nevezett kor az i. e. 11. századtól néhány száz évigtartó időszak, amit az irásbeliség hiánya miatt neveznek Sötét kor-nak. Az Achaemenid Birodalom idején (i. e. 550–330) Perzsiában néhány kiemelkedő könyvtár működött, amelyek két fő funkciót láttak el: adminisztratív dokumentumok nyilvántartását (pl. tranzakciók, kormányzati megbízások, költségvetés) és a források gyűjtése különböző témák szerint, pl. orvostudomány, csillagászat, történelem, geometria és filozófia. a kiégetett tableteket három fő nyelven írják: óperzsa, elámi és babilóniai (amorita) nyelven. Az ékírásos szövegek adás-vételekről, adókról, fizetésekről, kincstári adatokról és élelmiszerekről szólnak. A táblagyűjteményt Persepolis Fortification Archive néven ismerik, Irán tulajdona.

Egyes tudósok úgy vélik, hogy a macedón III. Sándor meghódítása után hatalmas archívumforrások és a tudomány különböző irányzataihoz tartozó források is átkerültek Perzsia fő könyvtáraiból Egyiptomba. Az anyagokat később lefordították latinra, egyiptomira, koptra és görögre, és figyelemre méltó tudományos gyűjteményt alkottak az Alexandriai Könyvtárban.

Az egyiptomi Alexandriai Könyvtár papirusztekercsei az ókori világ legnagyobb és legjelentősebb nagy könyvtárát alkották. A Ptolemaiosz-dinasztia idején virágzott, és a tudományok központjaként működött az i. e. 3. században történt felépítésétől egészen Egyiptom római meghódításáig, i. e. 30-ig. A könyvtárat vagy I. Ptolemaiosz Szóter (i. e. 323–283), és fia, II. Ptolemaiosz (i. e. 283–246) uralkodása idején tervezték és nyitották meg.

Az anatóliai ephesusi Celsus könyvtárát (ma Törökországban) Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus római szenátor tiszteletére építtette a fia i. u. 135-ben. A könyvtárat 12 000 tekercs tárolására építették, és Celsus monumentális sírjaként is szolgált. A könyvtár romjai -a kora középkorban elhagyták- Ephesus városának romjai alatt megmaradtak.

Görög és római könyvtárak

Pergamon, makett (Pergamon Múzeum, https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pergamon)

II. Eumenész nagy műveltségű uralkodó volt, aki az alexandriai könyvtár mintájára megalapította a pergamoni könyvtárat, a Pergamon Birodalom egyik nevezetes városa Trója volt. Az egyiptomi Ptolemaioszok a rivalizálás miatt megtiltották számára a papirusz kivitelét, ezért kitalálták a pergament, azaz az állati bőrből fehérített, vékonyított, kétoldalas írásra alkalmas lapokat. A pergamenlapokat, a korábbi tekercsekkel ellentétben, könyv formában lehetett tárolni. Így alakultak ki a kódexek (https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pergamon).

A klasszikus Görögországban csak az i. e. 5. században jelentek meg az írott könyvekből álló magán- vagy személyes könyvtárak (ellentétben a levéltárban őrzött állami vagy intézményi nyilvántartásokkal). A hellenisztikus ókor ünnepelt könyveit a 2. század végén sorolták fel Deipnosophistae-ban. A római könyvtárak: Augustus idejében a római fórumok közelében voltak nyilvános könyvtárak, a Marcellus Színház melletti Porticus Octaviae-ban, Apollo Palatinus templomában és a Traianus fórumának Ulpianus-könyvtárában. Az állami levéltárat a Forum Romanum és a Capitolium-hegy közötti lejtőn lévő épületben őrizték.

A magánkönyvtárak a késői köztársaság idején jelentek meg: Seneca az írástudatlan tulajdonosok által birtokolt könyvtárak ellen fordult, akik életük során alig olvasták el a címeiket, de a tekercseket elefántcsonttal kirakott citrusfából készült könyvespolcokban (armaria) helyezték el a mennyezetig: "most már a fürdőhöz és a melegvízhez hasonlóan a könyvtár is alapfelszereltség egy szép házhoz. A könyvtárak a villákhoz illő berendezési tárgyak lettek". Nevezetesek a tusculumi Cicero, Maecenas több villája, vagy az ifjabb Pliniusé, melyeket a fennmaradt levelek írnak le. A Herculaneumban található Papirusok villájában, nyilvánvalóan Caesar apósának villájában, a görög könyvtár részben a vulkáni hamuban őrződött meg.

Az első nyilvános könyvtárak

A Római Birodalom alatt jöttek létre. Minden sikeres császár egy vagy több könyvtár megnyitására törekedett, amelyek felülmúlták elődjének a könyvtárát. Róma első nyilvános könyvtárát Asinius Pollio alapította. Pollio Julius Caesar hadnagya és egyik lelkes támogatója volt. Az illíriai katonai győzelme után Pollio úgy érezte, van elég hírneve és vagyona ahhoz, hogy létrehozza azt, amit Julius Caesar* régóta szeretett volna: egy nyilvános könyvtárat, amely növeli Róma presztízsét, és vetekszik az alexandriaival. Az egyik első és kiadott, sokat olvasott könyv Caesar galliai naplója* lett. Pollios könyvtára, az Anla Libertatis, amely az Atrium Libertatisban volt, központi helyen, a Forum Romanum közelében volt. Ez volt az első olyan könyvtár, ahol görög és latin nyelvű könyveket elkülönítve tárolták, majd minden későbbi római közkönyvtárban is elkülönítették. Az építkezései során Augustus további két nyilvános könyvtárat hozott létre. Az első a Apollón-templom könyvtára volt, amelyet gyakran Nádori-könyvtárnak neveznek, a második pedig a Porticus Octaviae könyvtára volt. Sajnos a Porticus Octaviae könyvtár később megsemmisült egy katasztrofális tüzben, amely i.sz. 80-ban tört ki.

Tiberius császár további két könyvtárral bővítette a Palatinus-hegyet, egy továbbival Vespasianus i. u. 70 után. Vespasianus könyvtárát a Vespasianus Fórumában, más néven a Béke Fórumán építették fel, és Róma egyik fő könyvtárává vált. A Bibliotheca Pacis hagyományos mintára épült, és két nagy teremmel rendelkezik, amelyekben a görög és latin könyvtárak helyiségei voltak, amelyek Galenus és Lucius Aelius műveit tartalmazták. Az egyik legjobb állapotban fennmaradt ókori Ulpianus-könyvtár volt, amelyet Traianus császár épített. Az i.sz. 112/113-ban elkészült Ulpianus-könyvtár a Capitolium-dombon épült Traianus-fórum része volt. A Traianus-oszlop választotta el az egymással szemben álló görög és latin termeket. A szerkezet körülbelül ötven láb magas volt, a tető csúcsa pedig majdnem hetven métert ért el.

A görög könyvtárakkal ellentétben az olvasók közvetlenül hozzáférhettek a tekercsekhez, amelyeket egy nagy terem falába épített polcokon őriztek. Az olvasás és a másolás a teremben történt. A fennmaradt feljegyzések csak néhány esetet közölnek a kölcsönzésről.

A nagy római fürdők többsége egyben kulturális központok is voltak, könyvtárakkal.

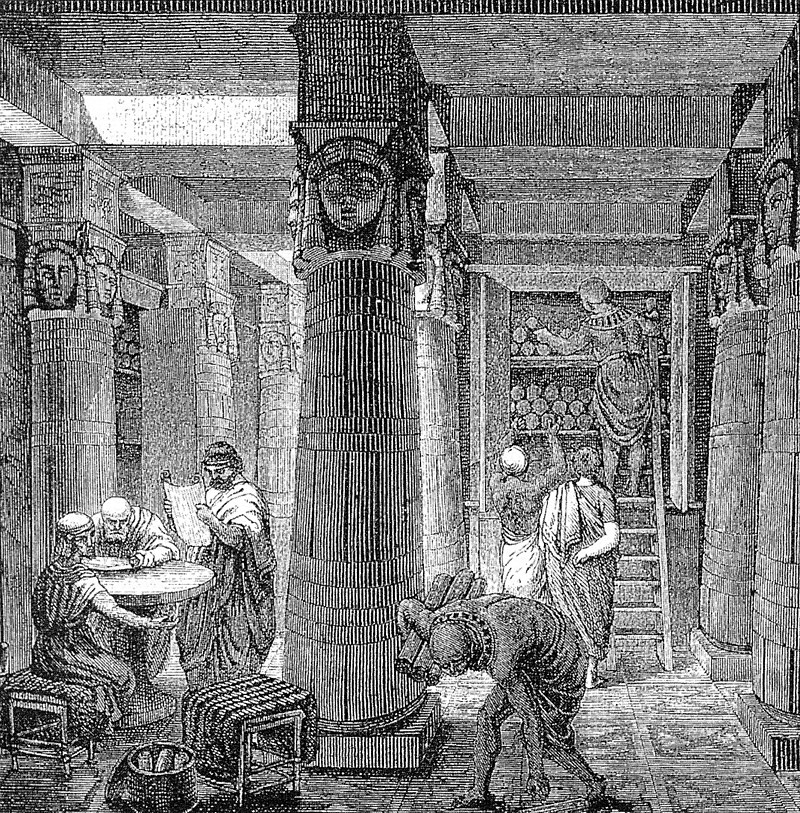

Rézkarc az alexandriai könyvtárról (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Library_of_Alexandria)

. A görögök az írásokat egy viszonylag kisebb helyiségben tárolták, ahová csak a személyzet mehetett be, hogy kihozza a kívánt pergameneket az olvasóknak, akik egy szomszédos teremben vagy fedett sétányon olvashattak. A katalógusokban szereplő művek többsége vallási jellegű volt. "A könyvtár számos esetben teljes egészében teológiai és liturgikus volt, és a könyvtárak nagy részében a nem egyházi tartalom nem érte el az összmennyiség egyharmadát". De egy időben Platón különösen népszerű volt, a korai középkorban Arisztotelész is. A könyvtári állományon belül képviselve voltak a latin szerzők is. Cicero különösen népszerű író volt, Vergilius a középkori könyvtárak többségében megtalálható volt. Az egyik legnépszerűbb Ovidius volt, amelyet körülbelül húsz francia és közel harminc német katalógus említ. Meglepő módon akkoriban még használtak régi római nyelvtani tankönyveket is.

Késő antik kor

Perzsiában a könyvek gyűjtése vonzotta az uralkodókat és a papokat az egész Szászánida Birodalomban (i.sz. 224-651), miután az ország politikai és gazdasági stabilitást ért el. A papok az egész területről összegyűjtötték a zoroasztrianizmus kéziratokat. Az uralkodók a tudományt népszerűsítették. Abban az időben sok zoroasztriánus tűztemplom könyvtárakkal együtt épült, a templomok a vallási tartalmak gyűjtésére és népszerűsítésére szolgáltak. A Gundeshapur Akadémia könyvtárból, kórházból és akadémiából állt. A könyvtári forrásokat gyarapítva az akadémia folyamatosan nagyköveteket küldött más földrajzi régiókba, pl. Kínába, Rómába és Indiába, hogy másolják le a kéziratokat, kódexeket és könyveket; fordítsák le őket pahlavira különböző nyelvekről, pl. szanszkrit, görög és szír nyelvből, és hozák vissza az Akadémiára.

Perzsiában a könyvek gyűjtése vonzotta az uralkodókat és a papokat az egész Szászánida Birodalomban (i.sz. 224-651), miután az ország politikai és gazdasági stabilitást ért el. A papok az egész területről összegyűjtötték a zoroasztrianizmus kéziratokat. Az uralkodók a tudományt népszerűsítették. Abban az időben sok zoroasztriánus tűztemplom könyvtárakkal együtt épült, a templomok a vallási tartalmak gyűjtésére és népszerűsítésére szolgáltak. A Gundeshapur Akadémia könyvtárból, kórházból és akadémiából állt. A könyvtári forrásokat gyarapítva az akadémia folyamatosan nagyköveteket küldött más földrajzi régiókba, pl. Kínába, Rómába és Indiába, hogy másolják le a kéziratokat, kódexeket és könyveket; fordítsák le őket pahlavira különböző nyelvekről, pl. szanszkrit, görög és szír nyelvből, és hozák vissza az Akadémiára.

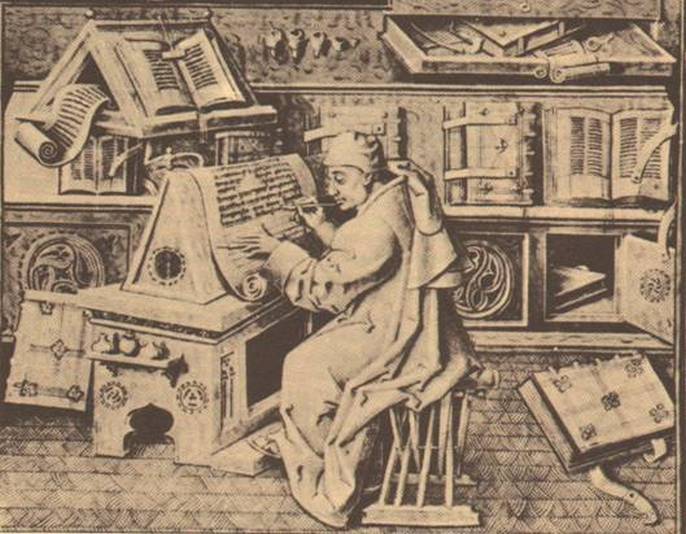

Kézírat másolása a kódexek korában (https://craham.preprod.lamp.cnrs.fr/)

A Cesenai Malatestiana Könyvtár, az első európai polgári könyvtár: a késő ókorban és a középkorban nem volt egy olyan Róma, amely évszázadokon át uralkodott a Földközi-tengeren, és létrehozott huszonnyolc közkönyvtárat. A Birodalom kettészakadt, majd később újra egyesült Nagy Konstantin vezetésével, aki i.sz. 330-ban áthelyezte a Római Birodalom fővárosát Bizáncba, amelyet Konstantinápolyra kereszteltek. Az ókorban virágzó római szellemi kultúra átalakuláson ment keresztül, ahogy az akadémiai világ a laikusoktól a keresztény papsággá vált. Ahogy a Nyugati kultúra összeomlott, a könyvek és könyvtárak keletre, a Bizánci Birodalomba költöztek, ahol négy különböző típusú könyvtár jött létre: császári, patriarchális, szerzetesi és magánkönyvtárak, és mert mindegyiknek megvolt a maga célja, a túlélésük is változatos volt.

Bizánci könyvtárak

A keresztény hívek közül sokan pogánynak tekintették a hellenisztikus kultúrát. Sok klasszikus görög mű, amely tekercsekre íródott, leromlott, mert csak a keresztény szövegeket tartották alkalmasnak arra, hogy kódexekben, a modern könyv elődjében megőrizzék. De a klasszikus görög és római szövegek közül sokat átmásoltak, a papírhiány miatt átírtak. Régi kéziratokat is használtak új könyvek kötésére a drága papír és az új papír hiánya miatt. Bizáncban a hellenisztikus gondolkodás kódex formájában való megőrzését szerzetesek végezték leíró szobákben, scriptoriumokban. A kolostori könyvtári szkriptoriumok virágoztak Keleten és Nyugaton, a rájuk vonatkozó szabályok általában ugyanazok voltak. A kopárság és a napfény (mivel a gyertyák tűzforrást jelentettek) a scriptorium fő jellemzői voltak. A szerzetesek naponta órákat másoltak, csak az étkezés és az imák szakították meg a munkájukat. A könyvtárakat majdnem kizárólag a szerzetesek oktatásának szentelték. Erényeket is láttak a görög klasszikusokban, sok görög alkotást lemásoltak, és így elmentettek. A Konstantinápolyi Császári Könyvtár az ókori tudás fontos letéteményese lett. II. Constantius a királyi palota egyik karzatán császári könyvtárat hozott létre. 24 évig uralkodott, ami a könyvek felhalmozódásával járt. Themistiust, a pogány filozófust és tanárt nevezte ki a könyvtárépítési program főépítészévé. Themistius merész programba kezdett egy birodalmi nyilvános könyvtár létrehozására, amely Konstantinápoly új szellemi fővárosának központi eleme lett. Olyan klasszikus szerzőket örzött meg, mint Platón, Arisztotelész, Démoszthenész, Izokratész, Thukidész, Homérosz és Zénón. Themeistius kalligráfusokat és mesterembereket bérelt fel a kódexek elkészítésére. Oktatókat is kinevezett, és egyetemi jellegű iskolát hozott létre a könyvtárában. II. Constantius halála után Julianus, a bibliofil értelmiségi, rövid ideig, kevesebb mint három évig uralkodott, nagy hatást gyakorolt a császári könyvtárra, és keresztény és pogány könyveket is keresett gyűjteménybe. Később Valens császár görög és latin írnokokat bérelt fel teljes munkaidőben a királyi kincstártól kéziratok másolására és javítására. A Konstantinápolyi Császári Könyvtár 5. századi csúcspontján 120 000 kötetes volt, és Európa legnagyobb könyvtára lett, de a 477-es tűzvész az egész könyvtárat felemésztette.

A patriarchális könyvtárak nem jártak jobban, sőt néha rosszabbul, mint a császári könyvtár. A Konstantinápolyi Patriarchátus Könyvtárát nagy valószínűséggel Nagy Konstantin uralkodása alatt alapították a 4. században. Teológiai könyvtár volt, amely már könyvtári osztályozási rendszert alkalmazott. Számos ökumenikus zsinat tárházaként is szolgált, mint például a niceai, az efezusi zsinat és a kalcedoni zsinatok. A könyvtárost és asszisztenseket foglalkoztató könyvtár eredetileg a pátriárka hivatalos rezidenciájában állhatott, tartalma megsemmisült, mivel a vallási összecsapások könyvégetésekhez vezettek.

A kis magánkönyvtárak közül sok az egyháztagok és az arisztokrácia tulajdonában volt. A tanárokról is ismert volt, hogy kis személyes könyvtáraik, valamint gazdag bibliofilek voltak, akik megengedhették maguknak a korszak díszes könyveit.

*

Caesart az egyik legjobb latin szónokkét és prózaíróként tartották számon. Cicero is nagyra értékelte Caesar retorikáját és stílusát, de csak Caesar háborús kommentárjai maradtak fenn. Néhány mondatot más műveiből egyes szerzők többször idéznek. Elveszett művei közé tartozik az apai nagynénje, Julia temetési beszéde és az "Anticato" című dokumentum, amelyben Catót támadta. Julius Caesar verseit is említik az ókori források.

Emlékiratai, a Commentarii de Bello Gallico, angolul The Gallic Wars néven ismernek. A hét könyv a Galliában és Dél-Britanniában az időszámításunk előtti 50-es években folytatott hadjáratainak egy-egy évét fedi le, a nyolcadik könyvet Aulus Hirtius írta az utolsó két évéről. A Commentarii de Bello Civili (A polgárháború), a polgárháború eseményeiről számol be riportokban Caesar szemszögéből, egészen Pompeius egyiptomi haláláig. Történelmileg további műveket is Caesarnak tulajdonítottak, de szerzőjük kétséges:

De Bello Alexandrino (Az alexandriai háborúról),

De Bello Africo (Az afrikai háborúról), hadjáratok Észak-Afrikában; és

De Bello Hispaniensi (A spanyol háborúról), hadjáratai az Ibériai-félszigeten.

De Bello Africo (Az afrikai háborúról), hadjáratok Észak-Afrikában; és

De Bello Hispaniensi (A spanyol háborúról), hadjáratai az Ibériai-félszigeten.

Naplója, riportjai lényegesek voltak Caesar képének kialakításában és hírnevének növelésében, amikor hosszabb ideig távol volt Rómától. Közszemlére tették ki az írásait. A tiszta és közvetlen latin stílus mintájaként a Gall Wars-t hagyományosan első- vagy másodéves latin hallgatók tanulmányozták.

A naplójában Julius Caesar leírja azokat a csatákat, hadjáratokat és eseményeket, amelyek a kelta és germán népek elleni harcban töltött kilenc év alatt történtek. Gyakran használja a „Gallia” szót a kelta és germán területekre, és gallként úgy, hogy a germán és kelta népeket „műveletlen” népeknek nevezte, mert a rómaiak a kelta népeket civilizálatlannak tartották. Julius Caesar naplója nyolc könyvét Rómában adták ki, azaz másolták i. e. 58 és i. e. 49 között. Úgy tartják, hogy Caesar, aki aktívan harcolt a kelta és germán törzsek ellen, egy írnokot (valakit, aki latin betűkkel írt) alkalmazott a beszámolók lejegyzésére, Caesar diktálta azokat. A kéziratait valószínűleg elküldték Rómába (Ravennában telelt sok éven át a Gall-háborúi idején), hogy másolják és kiadják az írásait. A könyvek mindegyike 5000 és 15 000 szó közötti terjedelmű. Rómában rendszeresen olvasott és megvitatott szöveggé váltak. Az utolsó könyvet Caesar halála után barátja, Aulus Hirtius írta.

Római könyvek és könyvmásolás: Amikor az író elkészült munkájával, a kész kéziratot átadta kiadójának, aki sok másolatot (https://mek.oszk.hu/01600/01650/html/fejez6.htm) készíttetett róla, hogy a lehető legszélesebb körben tudja az író művét terjeszteni. A könyveket ebben az időben még kézzel másolták, s egy-egy kiadónak sok könyvmásoló állt szolgálatában. A könyvmásolók rabszolgák voltak, s nagy részük Görögországból került Rómába. A kiadók a másoló rabszolgákért, különösen ha görögül is tudtak, magas árakat fizettek.

A könyvek másolásának módja rendszerint az volt, hogy valaki a szöveget hangosan diktálta, s egész sereg rabszolga egyszerre, ütemesen írta. Gazdáik végletekig kihasználták őket. A rabszolga másolók gyorsan és temérdek órán át dolgoztak naponta. Egy-egy kiadványból néhány nap alatt 3-400 példány is elkészült. Mivel gyakran előfordult, hogy a másolók hibákat ejtettek az írásban sok kiadó külön könyvmásolókat tartott, hogy azok a kézírásban előforduló hibákat utólag kijavítsák.

Az első római kiadót, akinek a neve is fennmaradt, Atticusnak hívták, aki barátja és kiadója volt Cicerónak. Nagyon gazdag ember hírében állt, akinek temérdek betanított rabszolga követte parancsát. A levelek közül, amelyeket Cicero írt Atticusnak, néhány még ma is megvan. Az egyik levélben például Cicero megtiltja Atticusnak, hogy művéből ki nem javított példányokat forgalomba hozzon. Egy másik levelében azt kérdezi Atticustól, hogy a hibát, amelyet ő, mármint Cicero, ejtett a kéziratában, kijavíttatta-e, mielőtt a kiadvány forgalomba került volna.

A könyvet alkotó tekercs göngyölt állapotban került a könyvtárba, s egy zsinóron csüngő kis lap (index, sillybes) tüntette fel a könyv tartalmát vagy címét. A kis lapoknak, amelyek rendszerint csontból készültek, az volt a rendeltetésük, mint a mai könyvgerinceknek. Az összegöngyölt tekercseket tokba helyezték. Ez a tok viszont a mai könyvek kötésének felelt meg.

A papiruszt hajókon szállították Egyiptomból Rómába. Minthogy pedig a papirusznövény kizárólag Egyiptomban termett, az ottani műhelyek e cikkekre világmonopóliumot élveztek. A világ tájára szállított papirusz elsőrendű áru volt, az egyiptomiaknak nem kellett versenytől tartaniuk, ezért alaposan meg is kérték az árát. A papirusz teljesen kész állapotban került szállításra. Készítési módja aránylag egyszerű volt. A növény szárának belét széles csíkokra vagdalták, ezekre keresztirányban még egy réteg csíkot dolgoztak rá, s e két réteg csíkot maga a növényi nedv, mint természetes ragasztóanyag, szétválaszthatatlan egésszé, ragasztotta össze. Hogy írásra alkalmassá tegyék, ugyanúgy, mint ma a papirost, enyvezték. Az enyvet lisztből, vízből és ecetből készítették. Az így előkészített papirusz lepréselték, megszárították, és amikor már minden nedvesség eltűnt, a kissé érdes felületét kagylóval vagy csonttal csiszolták. A kész papiruszlap teljesen sima felületű lett, a csíkoknak, növényi erezetnek még csak a nyoma sem látszott. Az ásatásokból előkerült papirusztekercsek is ilyenek, holott sok van közöttük, amely 3000 esztendős, nedvesség, féregrágás érte, de a rétegek felbomlásának legkisebb nyoma sem látható rajta.

A papiruszt hajókon szállították Egyiptomból Rómába. Minthogy pedig a papirusznövény kizárólag Egyiptomban termett, az ottani műhelyek e cikkekre világmonopóliumot élveztek. A világ tájára szállított papirusz elsőrendű áru volt, az egyiptomiaknak nem kellett versenytől tartaniuk, ezért alaposan meg is kérték az árát. A papirusz teljesen kész állapotban került szállításra. Készítési módja aránylag egyszerű volt. A növény szárának belét széles csíkokra vagdalták, ezekre keresztirányban még egy réteg csíkot dolgoztak rá, s e két réteg csíkot maga a növényi nedv, mint természetes ragasztóanyag, szétválaszthatatlan egésszé, ragasztotta össze. Hogy írásra alkalmassá tegyék, ugyanúgy, mint ma a papirost, enyvezték. Az enyvet lisztből, vízből és ecetből készítették. Az így előkészített papirusz lepréselték, megszárították, és amikor már minden nedvesség eltűnt, a kissé érdes felületét kagylóval vagy csonttal csiszolták. A kész papiruszlap teljesen sima felületű lett, a csíkoknak, növényi erezetnek még csak a nyoma sem látszott. Az ásatásokból előkerült papirusztekercsek is ilyenek, holott sok van közöttük, amely 3000 esztendős, nedvesség, féregrágás érte, de a rétegek felbomlásának legkisebb nyoma sem látható rajta.

A római kiadó az egyiptomi papiruszműhelyekkel állandó összeköttetésben volt. Szükségletéhez mérten különböző alakokra és minőségekre adta fel rendelését. Tudományos könyvekhez a nagyobb, költői művekhez a kisebb, kecsesebb alakokat hozatta. Plinius (i.sz. 23-79) feljegyzéseiből ismerjük a papirusz különböző minőségeit. Szerinte a legjobb minőségű volt a hieratica, amelyet később Augustus császár után Augustának neveztek, a következő jó minőségűt pedig a császár felesége után Claudiának. Más írók szerint a műhelyek földrajzi fekvése szerint kapták az egyes fajták neveiket. Saiticának pl. a Sais városa melletti gyár készítményeit nevezték.

Sok rómainak volt magánkönyvtára. Julius Caesar nyilvános könyvtárt is tervezett, de tervét már nem valósíthatta meg. Az első nyilvános könyvtárt i.e. 39-ben Gaius Asinius Pollio hadvezér, Caesar egykori bizalmasa alapította. A könyvtárak száma idők folyamán mindinkább nőtt, úgyhogy i.sz. 350-ben már 28 nyilvános könyvtára volt Rómának. E könyvtárak romjait később kiásták. Arról tehát tudomásunk van, hol voltak a könyvtárak de a papirusztekercsekből, amelyeket őriztek, nem maradt meg semmi.

Az egyetlen hely, ahol Egyiptomon kívül papirusztekercseket találtak, Herculaneum volt. Két római város, Pompeji és Herculaneum a Vezúv vulkán kitörő tüzes lávájának esett áldozatául, i.sz. 79-ben. Sok egyéb érdekes lelet között az egyik házban egy szobára bukkantak, amelynek falait körös-körül könyvespolcok övezték. A szoba közepén egy olvasóasztal állt, melyen az egykori olvasó kiteregethette tekercsét. A polcokon levő tekercsek annyira elszenesedtek, hogy csak nagy üggyel-bajjal lehetett egy részüket felnyitni és elolvasni. Antonio Pioggio már az 1750-es években sokat kibontott, máig több mint 800 tekercsből sok részletet olvastak el, és szövegeiket (köztük Epikurosz és Philodémosz azelőtt ismeretlen műveit) könyvekben is megjelentették.

**

Érdekesség (https://telex.hu/techtud/2024/09/08/internet-archive-szerzoi-jog-internet-archivalas-per): A könyvtárak története és a kézíratok másolása régen nem a szerzői jogtokról szólt, ma már igen.

FÜGGELÉK

ELVESZETT, LEÉGETT KÖNYVTÁRAK LISTÁJA (Eredete https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_destroyed_libraries):

| Image | Name of the library | City | Country | Date of destruction | Perpetrator | Reason and/or account of destruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Library of Ashurbanipal | Nineveh | Neo-Assyrian Empire | 612 BC | coalition of Babylonians, Scythians and Medes | Nineveh was destroyed in 612 BCE by a coalition of Babylonians, Scythians and Medes, an ancient Iranian people. It is believed that during the burning of the palace, a great fire must have ravaged the library, causing the clay cuneiform tablets to become partially baked. This potentially destructive event helped preserve the tablets. As well as texts on clay tablets, some of the texts may have been inscribed onto wax boards which, because of their organic nature, have been lost. |

|

Xianyang Palace and State Archives | Xianyang | Qin China | 206 BC | Xiang Yu | Xiang Yu, rebelling against emperor Qin Er Shi, led his troops into Xianyang in 206 BC. He ordered the destruction of the Xianyang Palace by fire.[6] |

|

Library of Alexandria | Alexandria | Hellenistic Egypt Roman Egypt |

Disputed | Disputed | Disputed,[7][8] see destruction of the Library of Alexandria. |

| Imperial library of Luoyang | Luoyang | Han China | 189 AD | Dong Zhuo | Much of the city, including the imperial library, was purposefully burned when its population was relocated during an evacuation.[9][10]: 460–461 | |

|

Library of Pantainos | Athens | Roman Greece | 267 | Heruli | It was destroyed in 267 AD during the Heroulian invasion and in the 5th century it was incorporated into a large peristyle building. |

|

Hadrian's Library | Athens | Roman Greece | 267 | Heruli | The library was seriously damaged by the Herulian invasion of 267 and repaired by the prefect Herculius in AD 407–412. |

| Library of Antioch | Antioch | Seleucid Empire Roman Syria |

364 | Emperor Jovian[11] | The library had been heavily stocked by the aid of the perpetrator's non-Christian predecessor, Emperor Julian (the Apostate). | |

|

Library of the Serapeum | Alexandria | Hellenistic Egypt Roman Egypt |

392 | Theophilus of Alexandria | Following the conversion of the temple of Serapis into a church, the library was destroyed.[12] |

| Library of al-Hakam II | Córdoba | Al-Andalus | 976 | Al-Mansur Ibn Abi Aamir & religious scholars | All books consisting of "ancient science" were destroyed in a surge of ultra-orthodoxy.[13][14] | |

| Library of Rayy | Rayy | Buyid Emirate | 1029 | Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni | Burned the library and all books deemed as heretical.[15] | |

| Library at Sázava Monastery | Sázava | Holy Roman Empire | c.1097 | Abbot Diethard | After the removal of the Slavonic Benedictines from Sázava monastery, the new abbot destroyed all books written in Old Church Slavonic.[16] | |

| Library of Banu Ammar (Dar al-'ilm) | Tripoli | Fatimid Caliphate | 1109 | Crusaders | Following Sharaf al-Daulah's surrender to Baldwin I of Jerusalem, Genoese mercenaries burned and looted part of the city. The library, Dar al-'ilm, was burned.[17] | |

| Library of Ghazna | Ghazna | Ghurid empire | 1151 | 'Ala al-Din Husayn | City was sacked and burned for seven days. Libraries and palaces built by the Ghaznavids were destroyed.[18] | |

| Library of Nishapur | Nishapur | Seljuk Empire | 1154 | Oghuz Turks | City partially destroyed, libraries sacked and burned.[19] | |

|

Nalanda | Nalanda | India | 1193 | Bakhtiyar Khilji | Nalanda University complex (the most renowned repository of Buddhist knowledge in the world at the time) was sacked by Turkic Muslim invaders under the perpetrator; this event is seen as a milestone in the decline of Buddhism in India.[20] |

| Imperial Library of Constantinople | Constantinople | Byzantine Empire | 1204 | The Crusaders | In 1204, the library became a target of the knights of the Fourth Crusade. The library itself was destroyed and its contents burned or sold. | |

| Alamut Castle's library | Alamut Castle | Iran | 1256 | Mongols | Library destroyed after the capitulation of Alamut.[21] | |

| House of Wisdom | Baghdad | Iraq | 1258 | Mongols | Destroyed during the Battle of Baghdad[22] | |

| Libraries of Constantinople | Constantinople | Byzantine Empire | 1453 | Ottoman Turks | After the Fall of Constantinople, hundreds upon thousands of manuscripts were removed, sold, or destroyed from Constantinople's libraries.[23] | |

|

Madrassah Library | Granada | Crown of Castile | 1499 | Cardinal Cisneros | The library was ransacked by troops of Cardinal Cisneros in late 1499, the books were taken to the Plaza Bib-Rambla, where most of them were burned.[24] |

| Bibliotheca Corviniana | Buda | Hungary | 1526 | Ottoman Turks | Library was destroyed by Ottomans in the Battle of Mohács.[25] | |

| Monastic libraries | England | England | 1530s | Royal officials | The monastic libraries were destroyed or dispersed following the dissolution of monasteries by Henry VIII. | |

|

Glasney College | Penryn, Cornwall | England | 1548 | Royal officials | The smashing and looting of the Cornish colleges at Glasney and Crantock brought an end to the formal scholarship which had helped to sustain the Cornish language and the Cornish cultural identity. |

| Records on Gozo | Gozo | Hospitaller Malta | 1551 | Ottoman Turks | Most paper records held on Gozo were lost or destroyed during an Ottoman raid in 1551.[26] The raid is said to have "led to the near total destruction of documentary evidence for life in medieval Gozo."[27] | |

|

Maya codices of the Yucatán | Maní, Yucatán | Mexico and Guatemala | 1562-07-12 | Diego de Landa | Bishop De Landa, a Franciscan friar and conquistador during the Spanish conquest of Yucatán, wrote: "We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they (the Maya) regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction." Only three extant codices are widely considered unquestionably authentic. |

|

Raglan Library | Raglan Castle | Wales | 1646 | Parliamentary Army | The Earl of Worcester's library was burnt during the English Civil War by forces under the command of Thomas Fairfax |

|

Załuski Library | Warsaw | Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth/German-occupied Poland (General Government) |

1794/1944 | Imperial Russian Army/Nazi German troops | After the Kościuszko Uprising (1794), Russian troops, acting on orders from Czarina Catherine II, seized the library's holdings and transported them to her personal collection at Saint Petersburg, where a year later it formed the cornerstone of the newly founded Imperial Public Library.[28] Parts of the collections were damaged or destroyed as they were mishandled while being removed from the library and transported to Russia, and many were stolen.[28][29] According to the historian Joachim Lelewel, the Zaluskis' books, "could be bought at Grodno by the basket".[28] The collection was later dispersed among several Russian libraries. Some parts of the Zaluski collection came back to Poland on two separate dates in the nineteenth century: 1842 and 1863.[28] Government of the re-established Second Polish Republic reclaimed in the 1920s some of the former Załuski Library holdings from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic following the Treaty of Riga. The original building was destroyed by the Germans during World War II. German soldiers also deliberately destroyed the collection (held in the Krasiński Library at the time - see below) during the planned destruction of Warsaw in October 1944, after collapse of the Warsaw Uprising.[30][31][29] Only 1800 manuscripts and 30,000 printed materials from the original library survived the war. After the war, the original building was rebuilt under the Polish People's Republic.[32]https://archive.org/details/burningbooksleve00rebe/page/166_166_33-0" class="reference" style="line-height: 1; unicode-bidi: isolate; white-space: nowrap; font-weight: normal; font-style: normal; font-size: 12.8px;">[33] |

|

Library of Congress | Washington, D.C. | United States | 1814 | Troops of the British Army | The library was destroyed during the War of 1812 when British forces set fire to the U.S. Capitol during the Burning of Washington.[34] This attack was retaliation for the burning of the Canadian towns of York and Niagara by American troops in 1813.[35] Soon after its destruction, the Library of Congress was reestablished, largely thanks to the purchase of Thomas Jefferson's personal library in 1815. A second fire on December 24, 1851, destroyed a large portion of the Library of Congress' collection again, however, resulting in the loss of about two-thirds of the Thomas Jefferson collection and an estimated 35,000 books in total.[36] |

| Several libraries | Mexico City and major Mexican cities | Mexico | 1856-1867 | Liberal troops and anti-clericalists | During and after the Mexican Reform War, under the liberal governments of Benito Juárez and Ignacio Comonfort, many convent libraries and Church owned school libraries were sacked or destroyed by Liberal troops and looters, most notably included San Francisco Convent Library, which had over 16,000 books (great majority of them were unique collections of Spanish colonial era productions), the library was totally destroyed. Other important libraries included San Agustín Convent Library, was looted and burned. The Carmen de San Ángel Convent and its library were also totally destroyed (with a few books recovered), other affected convent libraries to different degrees were those of Santo Domingo, Las Capuchinas, Santa Clara, La Merced and the Church owned school Colegio de San Juan de Letrán, among others, all of them in Mexico City. Similar events happened all over Mexico, especially in major cities. Besides books, other items such as altarpieces, unique collections of colonial period Baroque paintings, crosses, sculptures, gold and silver chalices (often robbed and melted) were also lost. Total estimates place the total of lost books and manuscripts at 100,000 by 1884.[37][38] | |

|

University of Alabama | Tuscaloosa, Alabama | United States | 1865-05-04 | Troops of the Union Army | During the American Civil War, Union troops destroyed most buildings on the University of Alabama campus, including its library of approximately 7,000 volumes.[39] |

| Mosque-Library | Turnovo, Bulgaria | Ottoman Empire | 1877 | Christian Bulgarians | Turkish books in a library were destroyed when the mosque was burned.[40] | |

|

Royal library of the Kings of Burma | Mandalay Palace | Burma | 1885–1887 | Troops of the British Army | The British looted the palace at the end of the 3rd Anglo-Burmese War (some of the artefacts which were taken away are still on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London)[41] and burned down the royal library. |

| Hanlin Academy Library | Hanlin Academy | China | 1900-06-23/4 | Disputed. Possibly the Kansu Braves besieging the west of the Legation Quarter, or possibly by the international defending forces. | During the Siege of the International Legations in Beijing at the height of the Boxer Rebellion, the unofficial national library of China at the Hanlin Academy, which was adjacent to the British Legation, was set on fire (by whom and whether deliberately or accidentally is still disputed) and almost entirely destroyed. Many of the books and scrolls that survived the flames were subsequently looted by forces of the victorious foreign powers. | |

|

Library of the Catholic University of Leuven | Leuven | Belgium | 1914-08-25/1940-05 | German Occupation Troops | The Germans set the library on fire as part of the burning of the entire city in an attempt to use terror to quell Belgian resistance to occupation.[42] The library caught again fire during the World War II German invasion of Louvain, Belgium.[43] |

|

Public Records Office of Ireland | Dublin | Ireland | 1922 | Disputed. Poss. deliberately by Anti-Treaty IRA or accidental ignition of their stored explosives due to shelling by Provisional Government forces.[44] | The Four Courts was occupied by the Anti-Treaty IRA at the start of the Irish Civil War. The building was bombarded by the Provisional Government forces under Michael Collins.[45] |

|

Several religious libraries | Madrid | Republican Spain | 1931 | Anarchists and anti-clericalists | In 1931, several groups of radical leftists and anarchists, with the complicit inaction of the Republican government, burned down several convents in Madrid. Most included important libraries. Among them, the Colegio de la Inmaculada y San Pedro Claver and the Instituto Católico de Artes e Industrias with a library of 20 000 volumes; the Casa Profesa with a library of 80 000 volumes, considered the second best in Spain at the time, after the National Library; and the Instituto Católico de Artes e Industrias, with 20 000 volumes, including the archives of the paleographer García Villada, and 100 000 popular songs compiled by P. Antonio Martínez. Everything was lost. |

|

Oriental Library (also known as Dongfang Tushuguan) | Zhabei, Shanghai | China | 1932-02-01 | Imperial Japanese Army | During the January 28 incident in the Second Sino-Japanese War Japanese forces bombed The Commercial Press and the attached Oriental Library, setting it alight and destroying most of its collection of more than 500,000 volumes.[46][47][48] |

|

Institut für Sexualwissenschaft | Berlin | Nazi Germany | 1933-05-?? | Members of the Deutsche Studentenschaft | On 6 May 1933, the Deutsche Studentenschaft made an organised attack on the Institute of Sex Research. A few days later, the institute's library and archives were publicly hauled out and burned in the streets of the Opernplatz. |

| National University of Tsing Hua, University Nan-k'ai, Institute of Technology of He-pei, Medical College of He-pei, Agricultural College of He-pei, University Ta Hsia, University Kuang Hua, National University of Hunan | China | 1937–1945 | World War II Japanese Troops | During World War II, Japanese military forces destroyed or partly destroyed numerous Chinese libraries, including libraries at the National University of Tsing Hua, Peking (lost 200,000 of 350,000 books), the University Nan-k'ai, T'ien-chin (totally destroyed, 224,000 books lost), Institute of Technology of He-pei, T'ien-chin (completely destroyed), Medical College of He-pei, Pao-ting (completely destroyed), Agricultural College of He-pei, Pao-ting (completely destroyed), University Ta Hsia, Shanghai (completely destroyed), University Kuang Hua, Shanghai (completely destroyed), National University of Hunan (completely destroyed).[49] | ||

|

National Library of Serbia | Belgrade | Yugoslavia | 1941-04-06 | Nazi German Luftwaffe | Destroyed during the World War II bombing of Belgrade, on the order of Adolf Hitler himself.[50] Around 500.000 volumes and all collections of the library were destroyed in one of the largest book bonfires in European history.[51] |

|

SS. Cyril and Methodius National Library | Sofia | Bulgaria | 1943–1944 | Allied bombing Allied air forces | |

|

Krasiński Library (housing special collections of the National Library of Poland, including the Załuski Library collection, as well as those of the Warsaw University Library and the Warsaw Public Library) | Warsaw | German-occupied Poland (General Government) |

1944 | Nazi German troops | The library was deliberately set ablaze by Nazi German troops in the aftermath of the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. The burning of this library was part of the general planned destruction of Warsaw.https://archive.org/details/burningbooksleve00rebe/page/166_166_33-1" class="reference" style="line-height: 1; unicode-bidi: isolate; white-space: nowrap; font-weight: normal; font-style: normal; font-size: 12.8px;">[33] |

|

Library of the Zamoyski Family Entail | Warsaw | German-occupied Poland (General Government) |

1944 | Nazi German troops | The library (which housed the collections of the former Zamoyski Academy) was deliberately set ablaze by the Nazi German troops in the aftermath of the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. The burning of this library was part of the general planned destruction of Warsaw. Depending on source, 1800 to 3000 items constituting only 1.5% to 3% of the original collection (albeit the most valuable part) survived, partially due to the fact that the troops burning the library did not notice the entrance to the basement at the rear side of the building.[52] |

|

Central Archives of Historical Records | Warsaw | German-occupied Poland (General Government) |

1944 | Nazi German troops | In the aftermath of the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, the archives (one of the pair of archives housing historical documents of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with the other located in Vilnius) were not only deliberately set ablaze, but the Nazi German troops also entered each of the nine accessible fire-proof vaults in the underground shelter and meticulously burned one after another (entrance to the 10th was blocked by rubble, thus saving its contents). Part of the general planned destruction of Warsaw.[53] |

| Multiple private libraries all over Tokyo. | Tokyo | Japanese Empire | 1945 | US army air force | US firebombing of Tokyo in May 1945 destroyed many private Japanese libraries such as the 40,000 volumes in Hasegawa Nyozekan's house.[54] The firebombing of Tokyo destroyed the majority of personal libraries there with many publications from before the war being permanently lost.[55] Firebombing damaged Keio university in Tokyo.[56] | |

| Warsaw Public Library | Warsaw | German-occupied Poland (General Government) |

1945 | Nazi German troops | Before the outbreak of World War II the library already contained 500,000 book volumes. In January 1945 it was set ablaze by retreating Nazi German soldiers. As a result, 300,000 books were destroyed, another 100,000 were looted.[57] | |

|

Raczyński Library | Poznań | German-occupied Poland (Reichsgau Wartheland) |

1945 | Nazi German troops | The retreating Nazi German troops planted explosives in the building and triggered detonation, demolishing the entire structure and burning 90% of the collection, while the remaining 10% were looted in advance. |

|

Lebanese National Library | Beirut | Lebanon | 1975 | Lebanese Civil War | The 1975 war fighting began in Beirut's downtown where the National Library was located. During the war years, the library suffered significant damage. According to some sources, 1200 of most precious manuscripts disappeared, and no memory is left of the Library's organization and operational procedures of that time. |

|

National Library of Cambodia | Phnom Penh | Cambodia | 1976–1979 | The Khmer Rouge[49] | Burnt most of the books and all bibliographical records. Only 20% of materials survived.[49] |

|

Jaffna Public Library | Jaffna | Sri Lanka | 1981-05-?? | Plainclothes police officers and others | In May 1981, a mob composed of thugs and plainclothes police officers went on a rampage in minority Tamil-dominated northern Jaffna, and burned down the Jaffna Public Library. At least 95,000 volumes – the second largest library collection in South Asia – were destroyed.[58] |

| Sikh Reference Library | Punjab | India | 1984-06-07 | Indian Army | Prior to its destruction by Indian troops, the library hosted a vast collection of an estimated 20,000 literary works, including 11,107 books, 2,500 manuscripts, newspaper archives, historical letters, documents/files, and others mostly on Sikhism and in the Punjabi language but also on other topics and in other languages.[59][60] Its destruction could have been a desperate act on failure to locate letters or documents that could have implicated the then Indian government and its leader Indira Gandhi.[61][62] | |

! ! |

Central University Library of Bucharest | Bucharest | Romania | 1989-12-2? | Romanian Land Forces | Burnt down during the Romanian Revolution.[63][64] |

| Oriental Institute in Sarajevo | Sarajevo | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1992-05-17 | Bosnian Serb Army | Destroyed by the shellfire during the Siege of Sarajevo.[65][66][67] | |

|

National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina | Sarajevo | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1992-08-25 | Bosnian Serb Army | The library was completely destroyed during the Siege of Sarajevo.[65] |

| Abkhazian Research Institute of History, Language and Literature & National Library of Abkhazia | Sukhumi | Abkhazia | 1992-10-?? | Georgian Armed Forces | Destroyed during the War in Abkhazia.[68][69] | |

| City library | Linköping | Sweden | 1996-09-20 | Lack of evidence for trial | After a year of repeated, minor arson attempts against an information bureau for immigrants located in the building, the library is eventually burnt down to the ground. | |

| Pol-i-Khomri Public Library | Pol-i-Khomri | Afghanistan | 1998 | Taliban militia | It held 55,000 books and old manuscripts.[70] | |

| Iraq National Library and Archive, Al-Awqaf Library, Central Library of the University of Baghdad, Library of Bayt al-Hikma, Central Library of the University of Mosul and other libraries | Baghdad | Iraq | 2003-04-?? | Unknown members of the Bagdad population | Several libraries looted, set on fire, damaged and destroyed in various degrees during the 2003 Iraq War.[71][72][73][74][75] | |

| The People's Library Occupy Wall Street | Zuccotti Park Lower Manhattan New York City | United States | 2011 | New York City Department of Sanitation | Over 5,000 books cataloged in LibraryThing were seized.[76] | |

|

Egyptian Scientific Institute | Cairo | Egypt | 2011-12-?? | Aftermath of street clashes during the Egyptian revolution | A first estimate says that only 30,000 volumes have been saved of a total of 200,000.[77] |

|

Ahmed Baba Institute (Timbuktu library) | Timbuktu | Mali | 2013-01-28 | Islamist militias | Before the library was burned down, it contained over 20,000 manuscripts with only a fraction of them having been scanned as of January 2013. Before and during the occupation, more than 300,000 Timbuktu Manuscripts from the Institute and from private libraries were saved and moved to more secure locations.[78][79][80] |

| Ratanda Public Library | Lesedi Local Municipality | South Africa | 2013-03-12 | Public riots | 1,807 library books, technological infrastructure including seven patron workstations, a photocopy machine and a large screen television.[81] | |

| Libraries of Fisheries and Oceans Canada | Canada | 2013 | Government of Canada headed by prime minister Stephen Harper | Digitization effort to reduce the nine original libraries to seven and save $C443,000 annual cost.[82] Only 5–6% of the material was digitized, and scientific records and research created at a taxpayer cost of tens of millions of dollars were dumped, burned, and given away.[83] Particularly noted are baseline data important to ecological research, and data from 19th century exploration. | ||

| Saeh Library | Tripoli | Lebanon | 2014-01-03 | Unknown | The Christian library was burned down, it contained over 80,000 manuscripts and books.[84][85][86] | |

|

National Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina (partially) | Sarajevo | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2014-02-07 | Seven Bosnian rioters suspected of having started the fire; two (Salem Hatibović and Nihad Trnka)[87] were arrested.[88] On 4 April 2014, Salem Hatibović and Nihad Trnka were released (although still under suspicion of terrorism), on conditions that they don't leave their places of residence and abstain from having any contact with each other. Both were also mandated to report to the police once every week.[87] |

During the 2014 unrest in Bosnia and Herzegovina large amounts of historical documents were destroyed when sections of the Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina, housed in the presidential building, were set on fire. Among the lost archival material were documents and gifts from the Ottoman period, original documents from the 1878–1918 Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as documentations of the interwar period, the 1941–1945 rule of the Independent State of Croatia, papers from the following years, and about 15,000 files from the 1996–2003 Human Rights Chamber for Bosnia and Herzegovina.[89][90]

In the repositories that were burnt, about 60 percent of the material was lost, according to estimates by Šaban Zahirović, the head of the Archives.[91] |

| Mosul University libraries and private libraries |

Mosul | Iraq | 2014-12-?? | Ongoing ISIL book burning | Book burning.[92] | |

| Libraries in Al Anbar Governorate | Al Anbar Governorate | Iraq | 2014-12-?? | Ongoing ISIL book burning | Book burning.[92] | |

|

Institute of Scientific Information on Social Sciences (INION) (partially?) | Moscow | Russia | 2015-01-29 | Unknown. | Fire spread to 2000 m2 in third Floor. The roof caved in. Additional water damage. Ambient temperature too high for self-freezing of damaged Works. The library contains 14 million books, including rare texts in ancient Slavic languages, documents from the League of Nations, UNESCO, and parliamentary reports from countries including the US dating back as far as 1789.[93] |

| Mosul public library (Central Public Library in Ninawa) |

Mosul | Iraq | 2015-02-?? | ISIL book burning | 8,000 rare old books and manuscripts. Manuscripts from the 18th century, Syriac books printed in Iraq's first printing house in the 19th century, books from the Ottoman era, Iraqi newspapers from the early 20th century.[94] | |

| Howard College Law Library, University of KwaZulu-Natal | Durban | South Africa | 2016-09-06 | FeesMustFall protestors | Law Library, including early Roman-Dutch law texts, burnt by protesters during confrontations with the police.[95] |

Natural disasters

| Image | Name of the library | City | Country | Date of destruction | Causes and/or account of destruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Royal Library of Portugal, Ribeira Palace | Lisbon | Portugal | 1755-11-01 | Great Lisbon earthquake |

| Imperial University Library in Tokyo, Max Müller Library, Nishimura Library, Hoshino Library | Japan | 1923-09-01 | An earthquake and the following fires.[49] In September 1923 Tokyo Imperial University library lost 700,000 volumes to the Great Kanto earthquake setting off fires.[96][97][98] | ||

| National Library of Nicaragua Rubén Darío | Nicaragua | 1931, 1972 | It was damaged in the 1931 earthquake. Another earthquake in 1972 caused damage.[99][100] | ||

|

Several libraries, archives, and museums[101][102] | Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, Thailand, Sri Lanka | 2004-12-26 | The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. See Library damage resulting from the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. |

Fire

| Image | Name of the library | City | Country | Date of destruction | Account of destruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Library of Celsus | Ephesus | Roman Empire | 262 | A fire caused by the 262 Southwest Anatolia earthquake or a Gothic invasion. |

| University of Copenhagen Library | Copenhagen | Denmark | 1728 October | Copenhagen Fire of 1728 | |

| Cotton Library | London, Ashburnham House | United Kingdom | 1731-10-23 | ||

| Library of Congress | Washington, D.C. | United States | 1814-08-25 | ||

| Birmingham Central Library | Birmingham | United Kingdom | 1879-01-11 | A fire broke out behind a wooden partition serving as a temporary wall during building operations.[103] The fire caused extensive damage, with only 1,000 volumes saved from a stock of 50,000.[103] | |

| University of Virginia Library | Charlottesville, Virginia | United States | 1895-10-27 | ||

| New York State Library | Albany, New York | United States | 1911-03-29 | ||

| National Library of Peru | Lima | Peru | 1943-05-10 | ||

| Jewish Theological Seminary of America library | New York City | United States | 1966-04-18 | Jewish Theological Seminary library fire | |

| Charles A. Halbert Public Library | Basseterre | Saint Kitts and Nevis | 1982[104] | ||

| St Michael's House | Crafers | Australia | 1983 | St Michael's House was destroyed as a result of the Ash Wednesday bushfires. The entire 40,000 volume library was lost including works from the 16th century.[105] | |

| Dalhousie University Law Library | Halifax, Nova Scotia | Canada | 1985-08-16 | A lightning strike caused a short circuit in the electrical system which started a fire that destroyed the top floor of the building which housed the library.[106] | |

|

Los Angeles Central Library | Los Angeles, California | United States | 1986-04-29 & 1986-09-03 | At 10:52 a.m. on April 29, 1986, a fire alarm alerted staff and patrons of a fire in the library's main building. Over 350 firefighters responded to the blaze, which burned for about 7 hours. An estimated 400,000 books were destroyed and an additional 350,000 materials suffered significant amounts of smoke and water damaged. The fire was determined to have begun on the fifth tier of the northeast stack.[107] |

|

Academy of Sciences Library | Leningrad | USSR | 1988-02-14 | The 1988 fire in the Library of the USSR Academy of Sciences (now Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences) broke out on Sunday, February 14, 1988, in the newspaper section on the third floor of the library. According to the library's acting director Valeriy Leonov, the fire alarm sounded at 8:13 pm, when the library was closed for visitors. By the time the fire was extinguished the following afternoon, it had destroyed between 190,000 and 300,000[108] books of the total 12 million housed. About 3.5 million volumes initially became damp due to firefighting foam. |

| Norwich Library | Norwich, England | United Kingdom | 1994-08-01[109] | On August 1, 1994, Norwich Central Library caught fire due to an electrical fault. Over one hundred firefighters responded as the flames escalated and smoke became visible from twenty miles away. Over 100,000 books and thousands of historical documents were destroyed.[110] | |

| Iraq National Library | Baghdad | Iraq | 2003-04-15 | ||

|

Duchess Anna Amalia Library | Weimar | Germany | 2004-09-02 | |

| Glasgow School of Art, Rennie Mackintosh Library | Glasgow, Scotland | United Kingdom | 2014-05-24 & 2018-06-15 | On May 24, 2014, a fire began inside the Charles Rennie Mackintosh building at the Glasgow School of Art. The Mackintosh Library was lost in the blaze; however all students and staff were directed to safety and no injuries resulted.[111] The fire began after gases from an expanding foam canister being used in a student project were ignited by a sparking projector. At the time of the incident, the building's recently installed fire suppression system was not yet operational.[112] While the Mackintosh building was under renovation following the 2014 fire, a second fire broke out around 11:15 p.m. on June 15, 2018. Larger in scale than the previous fire, the damages that resulted destroyed all of the building's renovation progress, as well as part of the school that had been left untouched by the first fire.[113] | |

| Institute of Scientific Information on Social Sciences (INION) | Moscow | Russia | 2015-01-31 | ||

| Mzuzu University Library | Mzuzu | Malawi | 2015-12-18[114] | In the very early hours of December 18, 2015, the Mzuzu University library caught fire. Although the library's wooden structure and carpeting spread the flames rapidly, students, staff, and firefighters on the scene attempted to rescue materials by carrying them out of the building and away from the flames. But by 5:00 a.m. the library collapsed, resulting in the loss of 45,000 volumes. Then a sudden rainstorm heightened the damage by soaking materials that had been carried out of the burning building.[115] | |

|

National Museum of Brazil | Quinta da Boa Vista in Rio de Janeiro | Brazil | 2018-09-02 | Not yet investigated. See National Museum of Brazil fire. Museum library was also destroyed. |

|

Jagger Library (partially) | Cape Town | South Africa | 2021-04-18 | Partially destroyed by the 2021 Table Mountain fire.[116] However, the library's fire detection systems stopped the destruction of the entire collection.[117] |

References

- ^ Fadhil, Muna (26 February 2015). "Isis destroys thousands of books and manuscripts in Mosul libraries". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Special Challenges - Fire and Fire Suppression". National Archives. 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ a b Fineberg, Gail. "Moving Toward a Safer Library. Compliance Office Issues Fire Safety Report," Library of Congress Information Bulletin 60 no. 3, 65, March 2001

- ^ L.A., "Inspection Scorches Fire Safety at LC," American Libraries, 32 no. 3 17–18, March 2001

- ^ a b c Fixen, Edward L. and Vidar S. Landa,"Avoiding the Smell of Burning Data," Consulting-Specifying Engineer, May 2006, Vol. 39 Issue 5, p47-51

- ^ Sima Qian. Records of the Grand Historian, Biography of Emperor Gaozu.

- ^ "The Alexandrian Library". New Advent. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard; Lloyd-Jones, Hugh. "The Vanished Library". The New York Review. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Chakra, Hayden (April 14, 2021). "The Yellow Turban Rebellion - 21 Years of Struggle". About History. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ de Crespigny, Rafe (2017). Fire over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty 23-220 AD. Leiden: Brill. p. 419. ISBN 9789004324916.

- ^ Dirk Rohmann, Christianity, Book-Burning and Censorship in Late Antiquity, (Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2016), 240.

- ^ John Edwin Sandys, A History of Classical Scholarship From the End of the Sixth Century B.C. to the End of the Middle Ages, (Cambridge University Press, 2011), 113.

- ^ Ann Christy, Christians in Al-Andalus:711–1000, (Curzon Press, 2002), 142.

- ^ Libraries, Claude Gilliot, Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, Index, ed. Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach, (Routledge, 2006), 451.

- ^ Mackensen, Ruth Stellhorn (January 1935). "Moslem Libraries and Sectarian Propaganda". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 51 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 93–94. doi:10.1086/370447. JSTOR 528860. S2CID 170296340. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Wolverton, Lisa (2001). Hastening Toward Prague: Power and Society in the Medieval Czech Lands. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-8122-3613-0.

- ^ Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Vol. II, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 69.

- ^ C.E. Bosworth, The Later Ghaznavids, (Columbia University Press, 1977), 117.

- ^ The Tomb of Omar Khayyâm, George Sarton, Isis, Vol. 29, No. 1 (July, 1938):16.

- ^ Sen, Gertrude Emerson (1964) The Story of Early Indian Civilization. Orient Longmans

- ^ Ibn Taymiyya, David Waines, The Islamic World, ed. Andrew Rippin, (Routledge, 2008), 382

- ^ George Lane, Daily Life in the Mongol Empire, (Greenwood Press, 2006), 88.

- ^ Robert S. Nelson, The Italian Appreciation and Appropriation of Illuminated Byzantine Manuscripts, Ca. 1200–1450, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 49 (1995): 209-210.

- ^ Mercedes Garcia-Arenal Rodriquez and Fernando Rodríguez Mediano, The Orient in Spain: Converted Muslims, the Forged Lead Books of Granada, and the Rise of Orientalism, transl. Consuelo Lopez-Morillas, (Brill, 2013), 41.

- ^ (DE)Edit Szegedi, Geschichtsbewusstsein und Gruppenidentität, (Bohlau Verlag, 2002), 223.

- ^ "Notarial Archives discovery: Documents from Gozo dating to 1431 saved from the bin". The Malta Independent. 23 May 2015. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019.

- ^ Abela, Joan (2016). "Unearthing Gozo's Lost Medieval Past". In Vella, Charlene (ed.). At Home in Art: Essays in Honour of Mario Buhagiar. Malta: Midsea Books. pp. 29–46. ISBN 9789993275985.

- ^ a b c d Witt, Maria (September–October 2005). "The Strange Life of One of the Greatest European Libraries of the Eighteenth Century". FYI France. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Lech Chmielewski. "In the House under the Sign of the Kings". Welcome to Warsaw. Archived from the original on 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ Maria Witt (September–October 2005). "The Zaluski Collection in Warsaw". The Strange Life of One of the Greatest European Libraries of the Eighteenth Century. FYI France. Archived from the original on 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ Rebecca Knuth (2006). Burning books and leveling libraries: extremist violence and cultural destruction. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 166. ISBN 0-275-99007-9.

- ^ "Dom pod Królami". warszawa1939.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- https://archive.org/details/burningbooksleve00rebe/page/166_166-33" style="margin-bottom: 0.1em; break-inside: avoid-column; counter-increment: mw-ref-extends-parent 1 mw-references 1; counter-reset: mw-ref-extends-child 0;">^ a b Rebecca Knuth (2006). Burning Books and Leveling Libraries: extremist violence and cultural destruction. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 166. ISBN 0-275-99007-9.

- ^ "Jefferson's Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. 2006-03-06. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library : An Illustrated History. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4.

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson's Library". Library of Congress. 11 April 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Tovar de Teresa, Guillermo (1990). La ciudad de los palacios: crónica de un patrimonio perdido, Volume 1. Editorial Vuelta. p. 14. ISBN 9789686258172.

- ^ Báez, Guillermo (2013). Historia Universal de la Destrucción de Libros. OCEANO. pp. 220–222.

- ^ Wolfe, Suzanne Rau (1983). The University of Alabama: A Pictorial History. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. pp. 57–59.

- ^ R.J. Crampton, A Concise History of Bulgaria, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), 111.

- ^ Bird, George W. (1897). Wanderings in Burma. London: F. J. Bright & Son. p. 254.

- ^ Kramer, Alan (2008). Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-84614-013-6.Gibson, Craig (2008). "The culture of destruction in the First World War". Times Literary Supplement. No. January 30, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ^ University of Louvain, International Dictionary of University Histories, ed. Carol J. Summerfield, Mary Elizabeth Devine, Anthony Levi, (Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998), 531.

- ^ Hill, J. R. (2003). A New History of Ireland Volume VII: Ireland 1921–84. Oxford University Press. pp. Chapter II p2. ISBN 978-0-19-161559-7.

- ^ Ferriter, Diarmaid (2010). The Limits of Liberty – Episode 1. RTÉ.